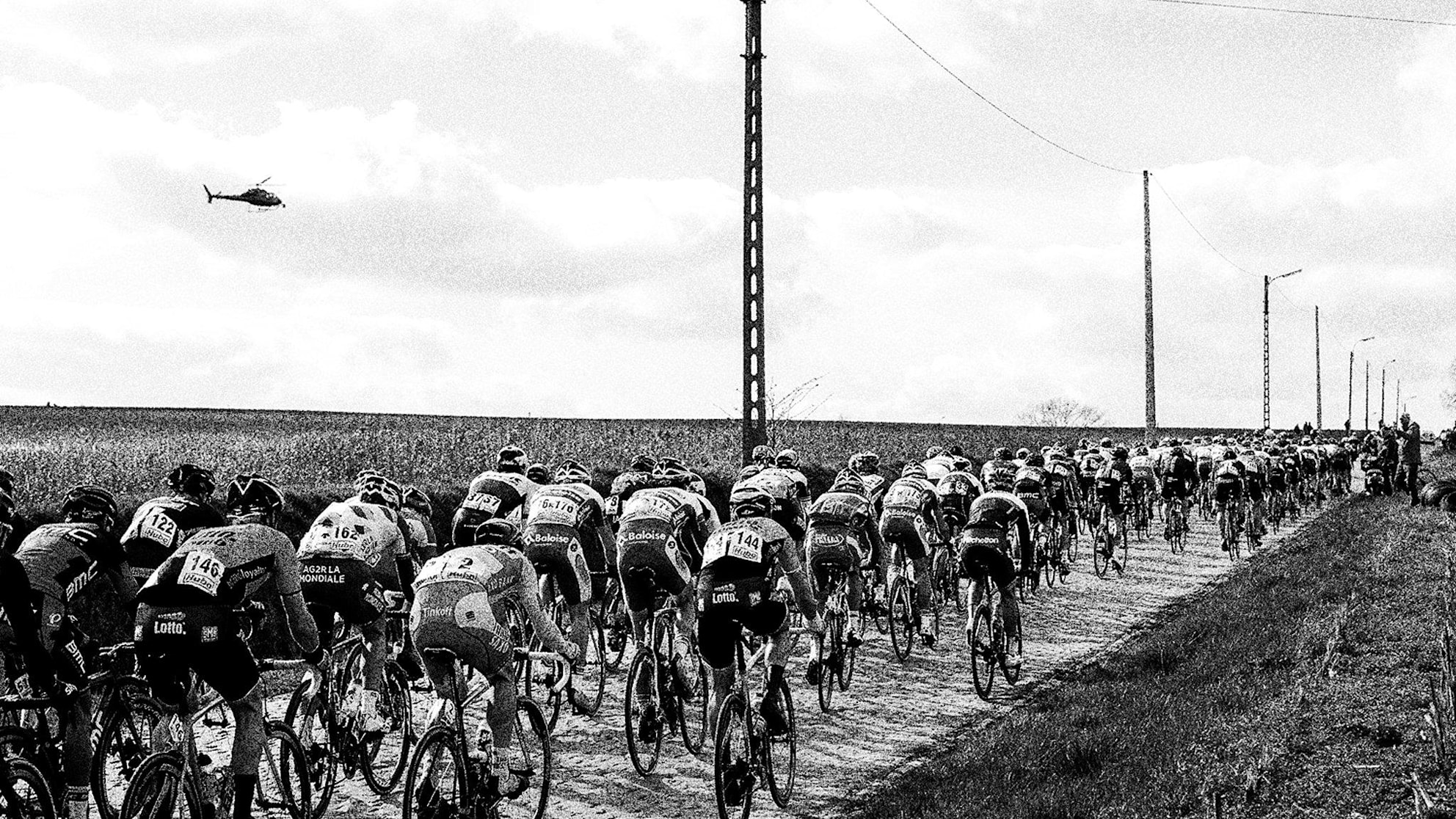

I count heads: it looks like the group is 40 riders, so I assume it is 60. There are always more than you think. The odds have changed, I think: 60 to one. I’m impressed.

And now my teammate Nico Hermans has looked around the group and seen me amongst the other dirtied faces. When he sidles up to me his eyes are wide and I know now that he is up for this one. He has hauled his large Flemish frame over La Houppe, Berg Stene and the Boigneberg and he is getting twitchy.

‘Hey, Rigo. I am good, I am good. Are you good?’ he pants.

‘Yeah, I’m good.’ I lie because I want him to have to think about asking me to work for him, but he won’t. He’s just as selfish as the rest of us, trampling each other underfoot to get our way.

“When the break gets caught, you go up the road, I’ll wait.”

Of course you fucking will. Never go first. Never.

I deflect. “I’ll go back to the car, and see what Pellecini says.”

Our sports director, Roberto Pellecini, will, I know, be next to useless. I raise my arm anyway and drop back to the car. I think of that very morning when he’d asked me the same thing that he’d asked me every day that I’d seen him: ‘Come sono le gambe?’

How are the legs? What a stupid fucking question, I thought. All I’ve done is walk out of my room to breakfast, how do I know how my legs are? They are still there, there is still blood flowing to them…

‘Bene’, I’d told him.

Pellecini is the scruffiest Italian I’ve ever seen, his shirt permanently untucked but always worn unbuttoned with a gold chain on display. He came to the team with the bike sponsor and the handful of Italian riders who had been amalgamated in uncomfortable fashion with the rest of the mix-mash of northern Europeans who had found themselves racing for Maspex–Nordeca. The lowest-ranked Division 1 team, it is the last bastion of the chancers and the desperate.

Pellecini skipped the team meeting the night before because his pregnant Belgian fiancée was waiting for him to go to dinner. He has a wife and daughter at home in Italy, of course. He was just happy he remembered to swap his wedding ring for his engagement ring. His life is a ticking time bomb and like most ex-pros it has been since the day that he retired from racing.

Now here he is with his head out of the window of our white Fiat barking like a dog.

I tell him the news, “Siamo rimasti in due.”

He pauses, as if counting to two is difficult.

“Farò quello che vuoi, voi due.”

‘Do what you want’ isn’t the answer I’m looking for.

He gives me four bottles.

“Ancora cinquanta chilometri.”