It ended, in the scorching heat of an unseasonably warm summer in eastern Europe, to the sound of Destiny’s Child. Eight days into his bid to once again become the fastest man across Europe, James Mark Hayden shuffled his way to a noughties album that could hardly have been more perfect. I'm a survivor, he hummed, as he buried himself in pursuit of Transcontinental glory.

The race, around which JMH has planned most of his life for several years, is a throwback to the sport's penchant for extraordinary feats. Its participants assemble somewhere in western Europe, most commonly the Belgian town of Geraardsbergen, and, at the sound of the gun, battle towards the continent's southeastern reaches. Riding an average of around 4,000 kilometres, crossing the most iconic mountain ranges in the world, they are always at war; with each other, themselves, the elements and the bike. There are no breaks, no relief from the jury's stopwatch, no downtime until the final pedal strokes towards the Aegean Sea. Once the Transcontinental starts, it does not stop until someone arrives in Greece. It is, for many, the pinnacle of ultra-endurance cycling, built as much for the love of the journey as the need to find the limits of human ability.

The limit, it turns out, lies somewhere around the 25kph mark. JMH arrived in Greece just over eight days after beginning the race at 10pm on Sunday, 29 July in Belgium. He had a meticulous game plan, learning from three years at the race and scrutinising every past foible, every personal strength. He would ride for around 20 hours a day, swapping the common decision to camp in bivouacs by the side of the road for three to four hours of guaranteed rest in guest houses and hotels along the way.

Every wink of sleep drags down the riders’ overall speed and JMH, like all of those at the sharp end of the race, marks rest as his chief rival. The race, therefore, becomes a mass exodus of the sleep deprived and the pig-headed. To win, total speed across the course matters first and foremost. 25kph seems around the magic number.

“Just because you’ve done well before, does not mean repeated success is a given. You have to come back with a completely new focus and treat it like a new race”

- JMH

Ultra-endurance racing has undergone a transformation in recent years with a new breed of fully dedicated and, to all extents, professional racers lining up to compete. JMH is at the vanguard of this select group alongside the likes of three-time Transcontinental winner Kristof Allegaert and the organiser of the Indian Pacific Wheel Race, Jesse Carlsson.

But, like every cyclist, there was a time when riding even short distances was beyond the man from Essex in England, who admits that he never thought he was capable of such. An energetic and athletic child, James was involved in various sports without becoming singularly obsessed with any of them. “I tried lots of different sports as a kid but never found anything that I clicked with, which is why I lacked that commitment sometimes”. Yet, as he admits, James has often felt a “chip on his shoulder” has always had a keen desire to prove himself. Not so much to others than to himself.

In contrast to the lofty heights he has now reached as an athlete, James’ journey to becoming a cyclist started when he moved away from home to study in Bristol, where he started riding his bike to get to and from lectures. After some time, he began to venture out of the city altogether on longer rides.

The first extended ride that JMH embarked upon was a trip to the shores of the Severn Estuary, north of Bristol. It might not be a long way to the coast, no more than fifteen miles each way but it is hilly, “I got out of the city and remember being confronted by a really steep hill – not too long but more than a match for me at the time. I struggled to the top where I collapsed off the bike and had to take ten minutes just lying on the verge to recover”, he recalls. Burning lungs, screaming legs, chest heaving, JMH knew that he had finally found his sporting niche.

“I knew straight away right then and there. I got up, rode on to the coast and, from then on, all I wanted to do was ride my bike more and more.”

Upon returning from university that summer, James’ almost continuous presence around the family home had become a source of irritation to other members of the household and it wasn’t long before his stepfather Chris intervened. Rather than lazing around the house, Chris suggested James should keep riding. “It was Chris who had given me the bike that I took to Bristol, he handed it back to me and told me to ‘clear off and take it with me’”, James chuckles. Equipped with a working bike and blessed with limitless time in which to ride it, that summer JMH began to really get into the sport, riding further and faster and swapping a t-shirt and shorts for some dedicated cycling kit.

As with so many riders led into the sport by an experienced hand, JMH’s stepfather became a regular source of motivation in his riding life. As well as providing him with his first road bike, Chris, himself an accomplished amateur cyclist, also kept James company on his first 100-mile ride and introduced him to the world of professional cycling. “I suppose he’s the one to blame really”, laughs James. “Without him I wouldn’t be aware of the sport at all, as no one else had ever spoken to me about it before or tuned in to watch a race with me. He’s still my number one fan”, James continues before stopping himself abruptly, “actually no, that has to be my mother Tamsin but Chris comes in a close second”.

Soon after discovering cycling, JMH switched universities, moved back to London and decided to join a cycling club. Located a stone’s throw from his Streatham Hill apartment is the Herne Hill velodrome, a historic hub for the city’s track cyclists and one of the last remaining venues used in the 1948 Olympic Games. With such easy access, JMH took up track racing, even notching up a win in a keirin race – a short, hectic discipline where riders draft behind a derny bike. Early accomplishments notwithstanding, pursuits on the track would ultimately provide little appeal for the rider.

It was in a time trial event that James was noticed by a local cycling club. Competing on a standard road bike against riders equipped with aerodynamic time trial machines, he managed to take a commanding win. So impressed were the organisers from Catford Cycling Club, that soon afterwards JMH was asked to join the club’s junior development team. As it turned out, the timing could hardly have been better.

To begin with, Catford’s junior set up was much like that of any other local cycling club, a relatively small, low-key affair that would send riders to compete in local races. That all changed when another Catford CC member, Jeff Banks, got involved and invested in the junior team with the ambition of competing at a higher level. James remembers the mixture of excitement and unpreparedness well, “before I knew it I was travelling around the UK, racing Elite Series events, the top tier of domestic racing. It was absolutely mad, particularly for someone who’d only started riding two years previously.”

“I broke bones all the way down my left side”

“I was completely taken aback by the sheer speed of the racing at that level and almost invariably got dropped from the bunch. In retrospect, I’m not sure how good it was for my development as a cyclist to be thrown in at the deep end like that.” At the end of the following season, his second as a competitive racer, JMH gave himself an ultimatum and resolved to try everything in order to improve his race results or, failing that, move on and try something else.

In the end, misfortune made his decision for him as he endured a nightmare season the following year. “I suffered a really bad crash while out training on my local roads just outside London in Kent”, James recounts. “I broke bones all the way down my left side, which resulted in over a month off the bike. Season ruined. I was on quiet country lanes where there are hardly any pavements yet still managed to hit a kerb. It must have been the only one for miles.” By that point, JMH had become somewhat bored with road racing anyway, “the reality is that you spend more time sitting in the car on the way to a race than you do on your bike racing”, he observes. “If you get dropped early on – we’ve all been there – then it feels all the more pointless.”

As an antidote to racing, JMH had begun to go touring at the end of each season. “It’s important to make the distinction between touring and bikepacking here”, he notes, “I would load up an old steel bike with panniers and pack a tent and camping equipment before heading off into the mountains, and this wasn’t the kind of touring most people do either. I wasn’t doing a bit of riding either side of a four-hour lunch, I was really pushing my limits with long days in the saddle.”

It was on one such touring expedition, while considering his next steps, that James began to think more seriously about long-distance endurance racing. He had heard of the Transcontinental and wanted a challenge that could satisfy his desire to ride long distances and provide the excitement of competition, but, like most people, had his doubts about whether he was capable.

As the racing season drew to a close that year, JMH decided one day to eschew his usual training regimen and, instead, embark upon a huge loop that would see him circumnavigate the outer reaches of London, a 200-mile round trip, twice as far as he had ever ridden before. It took him twelve hours to complete but upon his return that evening, he knew that everything was going to change. Having proven to himself that he could ride longer distances than he had ever thought he could, his transcontinental journey had begun.

“I would load up an old steel bike with panniers and pack a tent and camping equipment before heading off into the mountains”

- JMH

Three years later, JMH took to the starting line as an experienced veteran, defending champion and a hot favourite to clinch his second title. Yet, in his three previous participations at the race, James had experienced the soaring heights and the darkest depths of ultra-endurance racing, with a broad range of results to match.

Attempting the Transcontinental for the first time in 2015, JMH was struck down by a condition known to few apart from endurance athletes: Shermer’s neck. Unable to support the weight of his head, James’ neck muscles had completely failed as a result of fatigue and he was forced to scratch. Unbowed by his initial experience, JMH returned to the race with a vengeance the following year, finishing fourth despite suffering a chest infection that forced him to remain at the first checkpoint for 36 hours. After declaring himself fit to ride on, JMH set about clawing back the time that he had lost to his rivals and eventually passed all but three of them.

After the realisation in 2016 that he had the physical capacity to be competitive, fortune finally favoured JMH the following year as he enjoyed his first clean run at the race. Free from the illnesses and mechanical woes that had hindered his two previous attempts, he finished in just over nine days to take his maiden Transcontinental victory.

“you have to refocus, otherwise you’ll get complacent, you’ll overestimate your ability or something will go wrong.”

Back on the startline at this year’s race, however, JMH took nothing for granted, even with the number one emblazoned on his cap as the previous year’s winner. “Each race is a new challenge” he reaffirms, “you have to refocus, otherwise you’ll get complacent, you’ll overestimate your ability or something will go wrong.” All the talk at the start was of the intense heat that lay in wait and the possible repercussions the conditions could have for the race and its participants. James was typically stoic: “Yeah, this year is going to be hot”, he told us before the race, “but I’m well used to that and it might not be as hot as last year when the temperature reached 50 degrees in Serbia. I was riding through the night in just my jersey and bibs which is unheard of. I think this year temperatures are set to rise to around 40 degrees, which is hot, but kind of cool for me after last year.”

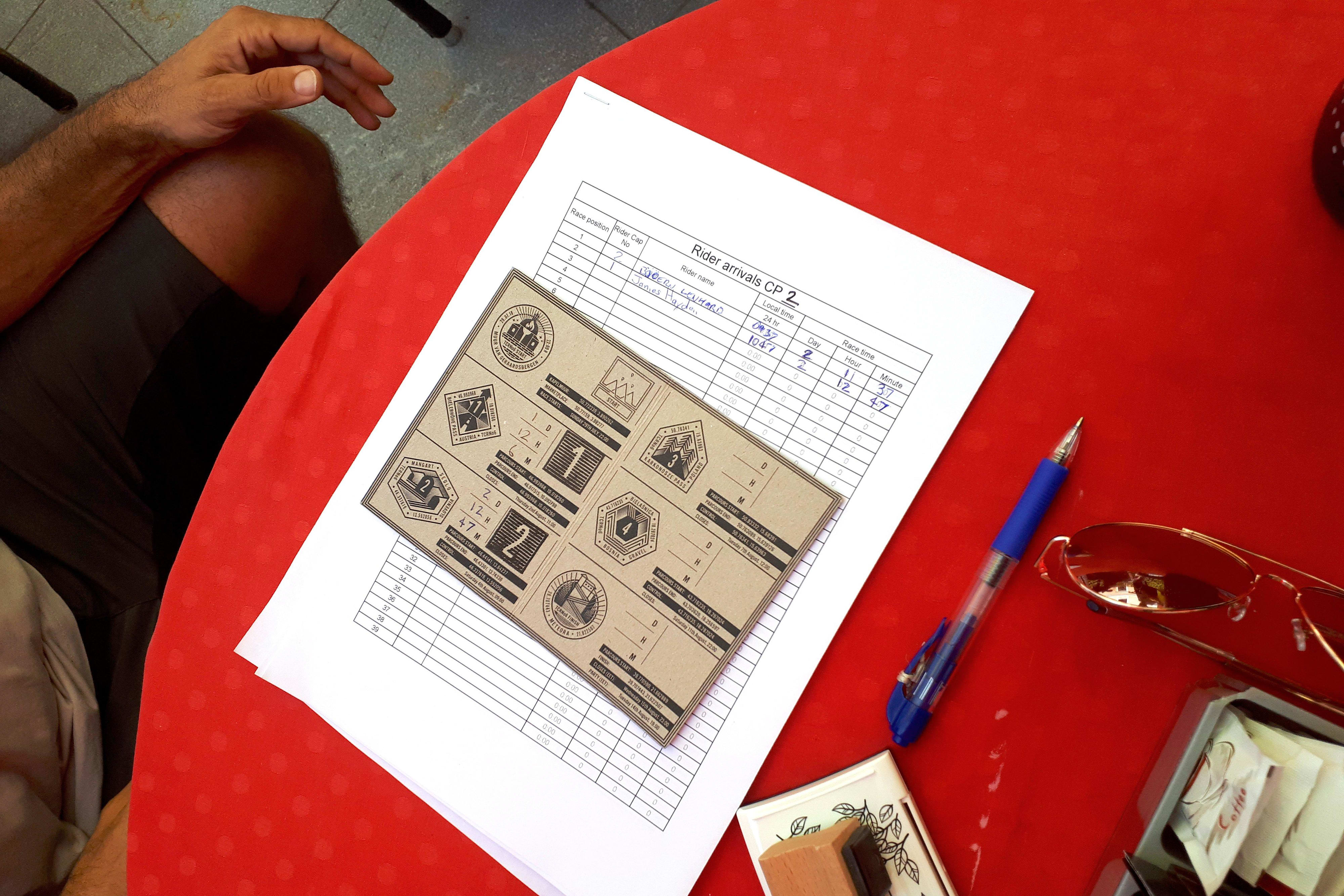

In the end it was a relief to be underway, all the pre-event hype and apprehension quickly giving way to a single-minded focus on the task at hand. Setting off up the hallowed slopes of the Muur van Geraardsbergen – a steep cobbled climb that often features in the Tour of Flanders each April – the initial goal was the first checkpoint atop the Bielerhöhe Pass in Austria. Since the race is a mass start, the first day of riding tends to throw up more chance encounters with competitors than the latter stages of the race. Towards the end of his first full day on the road, James came across longtime rival and friend Björn Lenhard. “I’d had a chance encounter with Björn on a previous edition of the Transcontinental when we bumped into each other at a petrol station”, says James. “This time I came across him on the road and we continued together for a few miles, just chatting. It was really interesting to note the differences in our routes; he had racked up fewer metres of elevation”, James notes, “but he had also ridden ten kilometres more”, he adds with a wry smile.

To stay at the sharp end of the race, riders are in the saddle for most of the day but, as James was at pains to impress, the Transcontinental is a challenge far more akin to a marathon than a sprint. Having built up a wealth of experience in previous years, James has a few strategies to help him sustain his effort. “If there are steep climbs on my route, I will try to make sure I tackle them later in the day. Getting up steep grades with the additional weight of your frame bags is slightly easier if you are already warm and your muscles are firing”, he observes. A case in point was the broken mountain road to the second checkpoint at the Karkonosze Pass in Poland, a climb whose steepest sections hit well over 25%. “I really struggled to keep the pedals turning”, he recalls painfully, “if I had stopped midway up the climb, I’d never have got going again. I reached the bottom of the pass in the early hours of the morning at the end of a long day but knew that I had to plough on to finish the day off and save myself from a rude awakening the next morning.” Another sage piece of advice James has for prospective participants of the Transcontinental is that it is sometimes faster to go slower, as proven on the descent of that same climb. “I took it easy rolling back down into the Czech Republic as I know from experience that bombing down a rough gravel road might save time in the short run but the ensuing punctures will soon erase those gains and then some.”

Consistency is a key component of success in ultra-endurance racing. When asked what his darkest moment of this year’s race was, James replied, “I didn’t really have any truly awful moments, it’s all about levelling out the peaks and the troughs, the highs and the lows.” Only one hiccup stuck out in his mind as a particularly trying one, caused by an inopportune puncture while riding through Bosnia. “I was riding yet another rough road when, unsurprisingly given the surface, my tyre went flat. I was in the mountains, nearly 2000 metres up with the evening light fading fast around me. It was not somewhere I wanted to be stranded with no option but to walk down the mountain in cycling shoes.” But, after a few minutes of scrabbling around in the dark for his tools, he had fixed the puncture and completed the remainder of the descent. “I booked a hotel room for the night and knew that I had one of the most challenging sections of the race route under my belt, it was a high point and a low point all in the space of an hour or two. A microcosm of the whole race.”

On the eighth and final day of his ride, as he powers through the Greek countryside, JMH knows that, barring incident, he is en route to victory. And what a victory, the length of Albania separates him from his nearest rival. With 100 kilometres remaining he rings ahead to pre-order a souvlaki kebab, a special celebratory treat and welcome relief from the uninterrupted stream of service station food that has kept him rolling for the last week. All is firmly under control.

Yet, despite his undisputed dominance on the bike, JMH assures us that it is not for the accolades that he does the TCR, but purely to prove a point to himself. “The finishing line is not about popping champagne, in fact, you’re normally so tired that the last thing you want is for someone to make a big deal of it.” This year, James was greeted at the finish line by his partner Isabelle, mother Tamsin, stepfather Chris and his sister. Just a small group of those closest to him, no fanfare and no victory speech.

For his competitors, he has only respect and admiration, “Most people on the TCR are very down-to-earth, straight forward characters”, he says, “no one is doing it for likes on Instagram and there is a strong mutual respect between all the riders.” So strong is the sense of camaraderie between fellow racers that, insistent on congratulating competitors and friends, JMH returned to the finish line numerous times after he had finished.

As for the next step, James is undecided but knows his future lies in long distance racing. With two Transcontinental race victories in his frame bag, there seems to be no challenge beyond his physical capabilities and we look forward to ‘following the dots’ on his next ultra-endurance adventure. But for now, we hope he’ll take a break and enjoy some time off the bike. He promised he would.